photo: ©2019 Mike Belleme

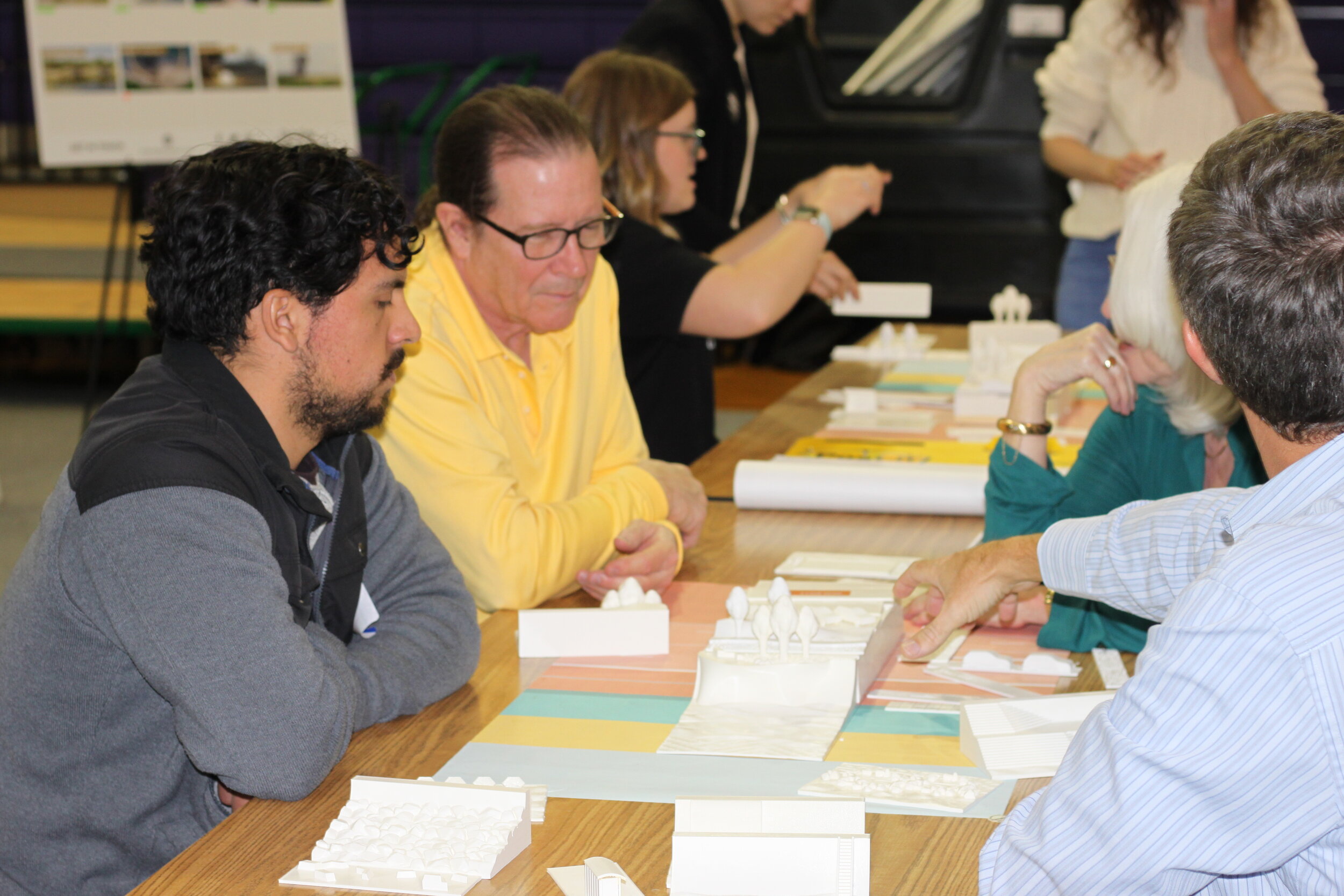

For planning projects at the city-scale, civic engagement is an essential tool to empower the public to actively participate in envisioning the future of their communities. If done authentically, with an open mind and a willingness to make it comfortable for people to share their stories, the process can be informative and provide a much-needed context regarding the complexities inherent in making urban design choices. The best engagement strategies are people-centric, hands-on, and creative.

A recent resiliency project in Galveston, Texas, offers a peek at how these types of gamified engagement exercises can both inform the design team and thoughtfully engage the public. Galveston is built on a barrier island in the Gulf of Mexico and is a small city with a history of hurricane devastation, most notably in 2008 when hurricane Ike made landfall. A 13-foot storm surge flooded nearly the entire island and in the immediate aftermath, the City’s population dropped from 57,000 to 48,000.

The project began with an ambitious goal; to develop a community vision plan for Galveston by engaging at minimum 15% of the population. The team, a collaboration between Huitt-Zollars, Asakura Robinson, Mass Economics and Stoss proposed several initiatives that ultimately led to ‘Vision Galveston’, the framework plan that was developed through three rounds of public outreach. Throughout the process, the engagement team focused on involving as many as people as possible, especially the traditionally underrepresented, seeking groups that represented the diversity of Galveston in age, race, sex, and geography.

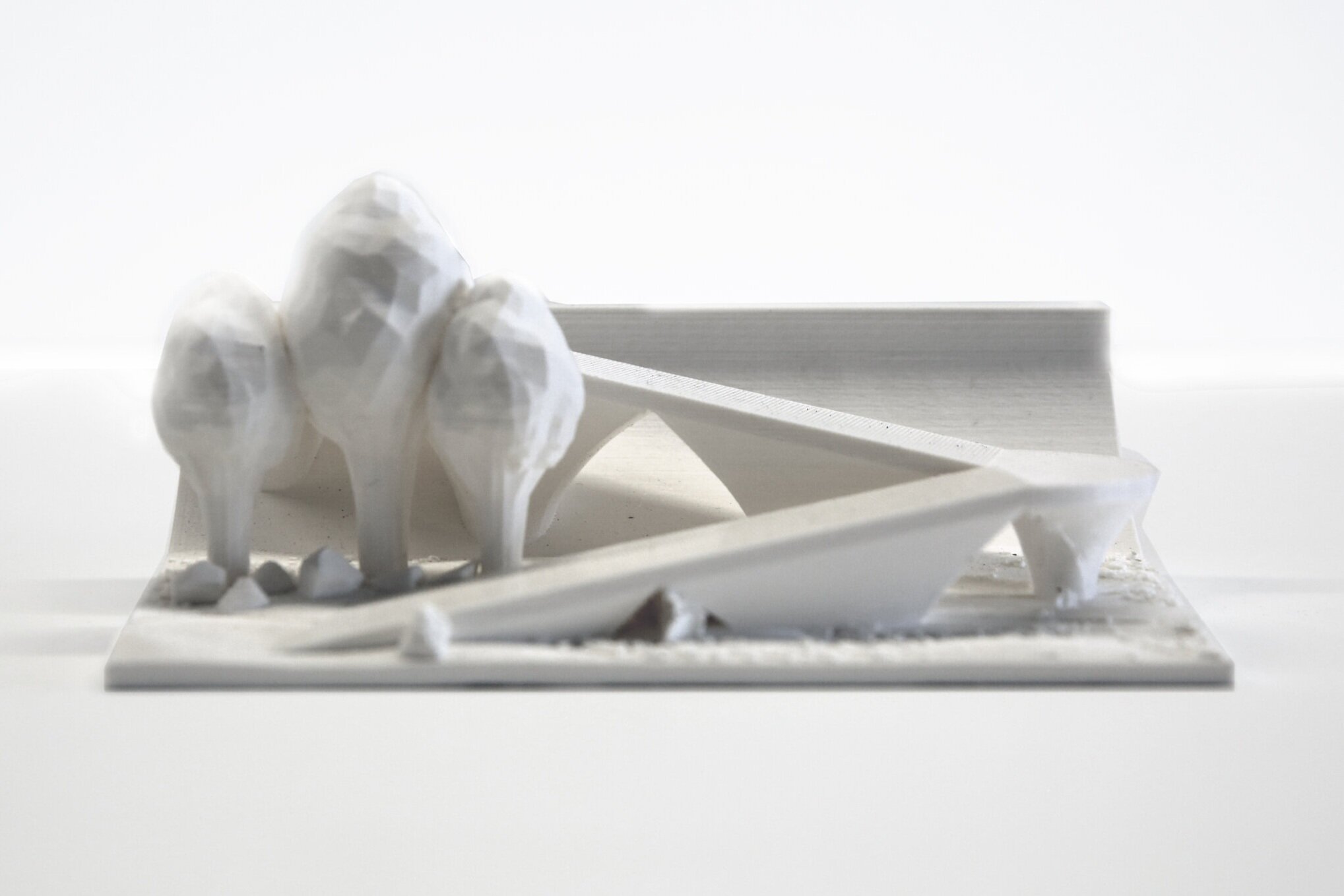

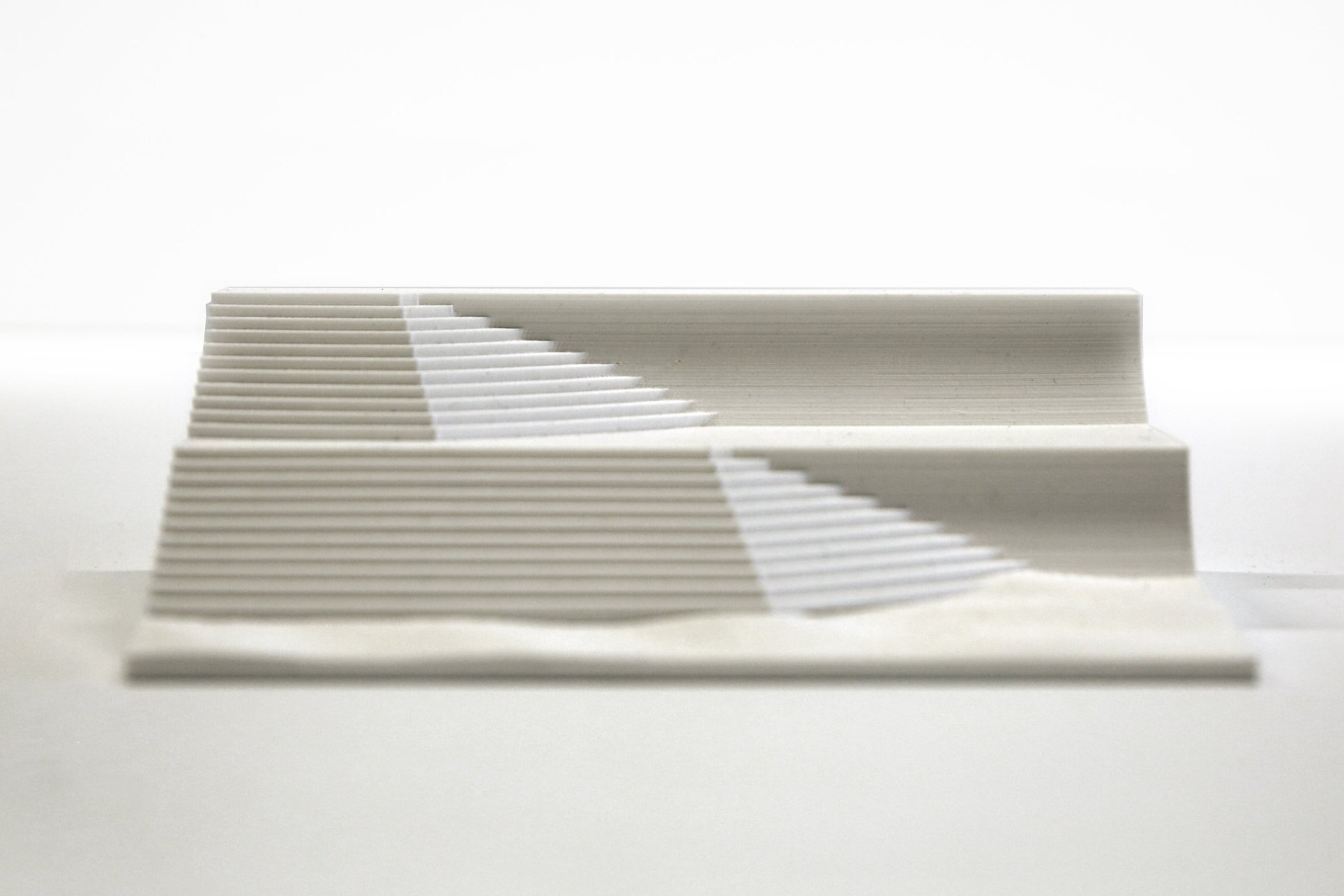

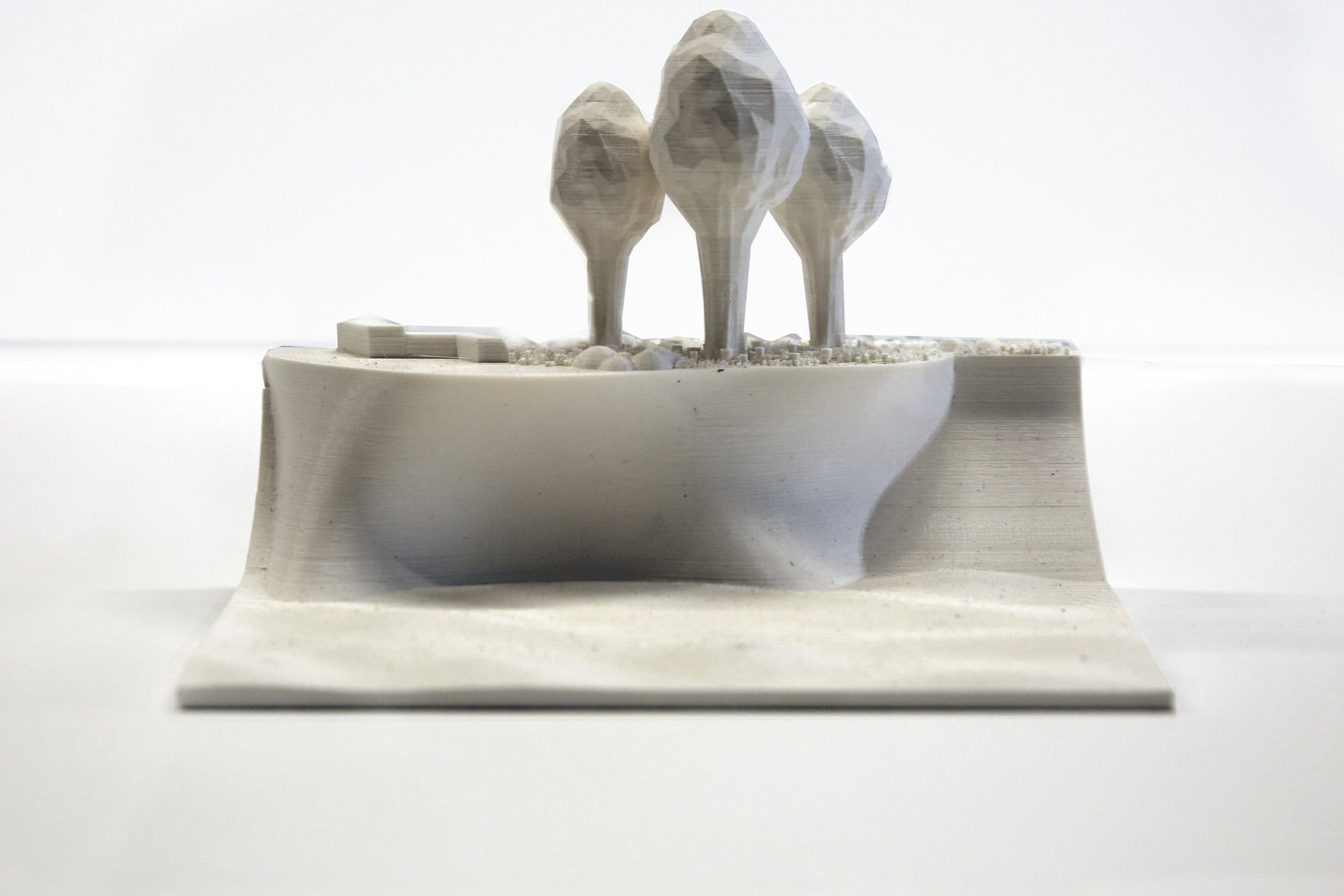

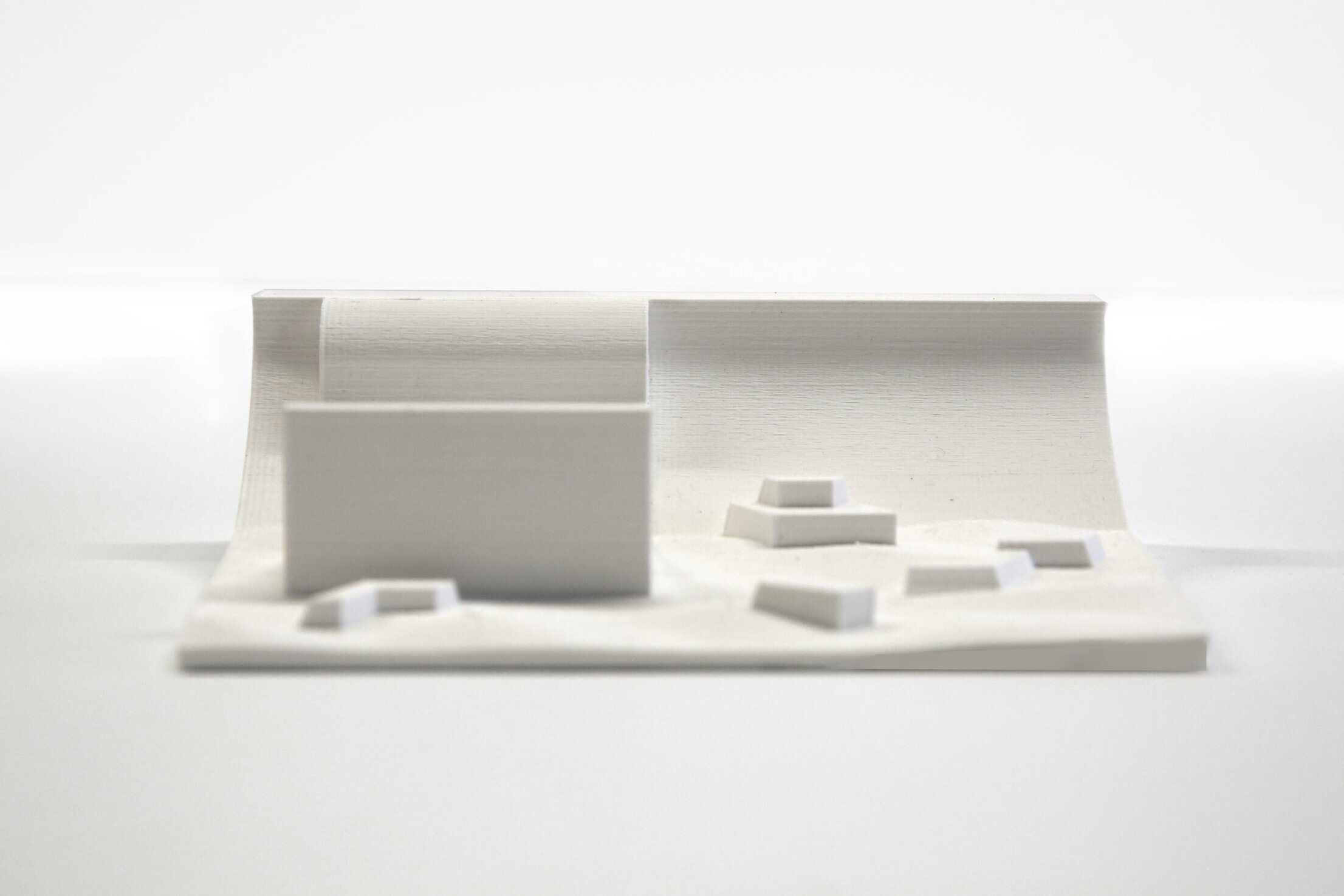

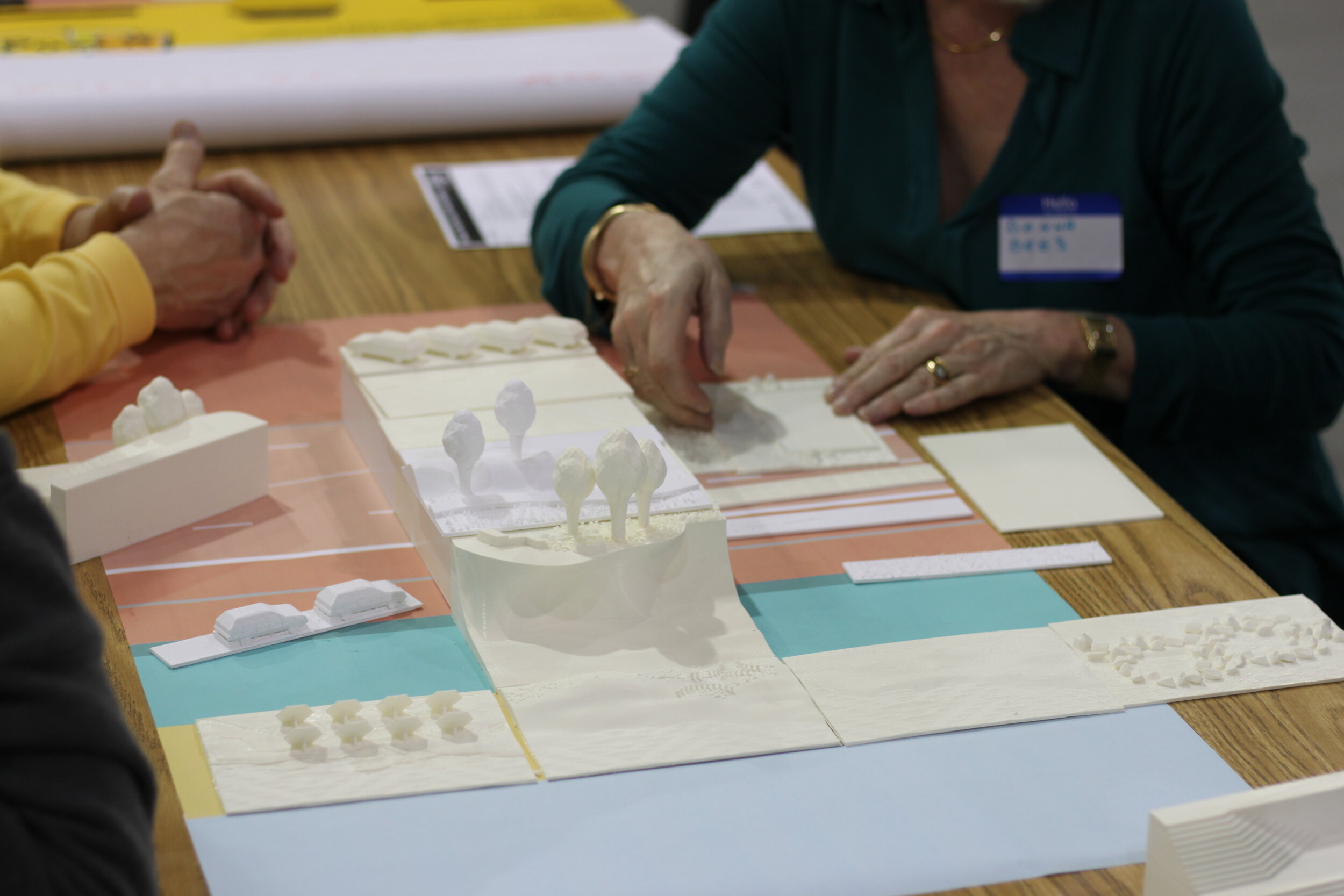

One of the highlights of the engagement process was an interactive exercise that involved developing a series of 3D printed seawall options that people could shuffle in order to design their ideal promenade, seawall and beach configuration. The seawall, a 10-mile long concrete barrier protecting downtown Galveston from tropical hurricanes, is central to Galveston’s identity and much beloved by the community. In fact, the Seawall is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. According to the report, “Recommendations and concerns regarding the Seawall were raised during the outreach process. This included requests for better access—more parking, free parking, improved connection to public transit, and safe crossings across the busy Seawall Blvd. … There were requests for better amenities for recreational activities along the boulevard and diversifying the land use and businesses across the street from the beach. Since the Seawall is central to the identity of Galvestonians, many people requested further beautification to the Seawall, using landscaping and other means.”

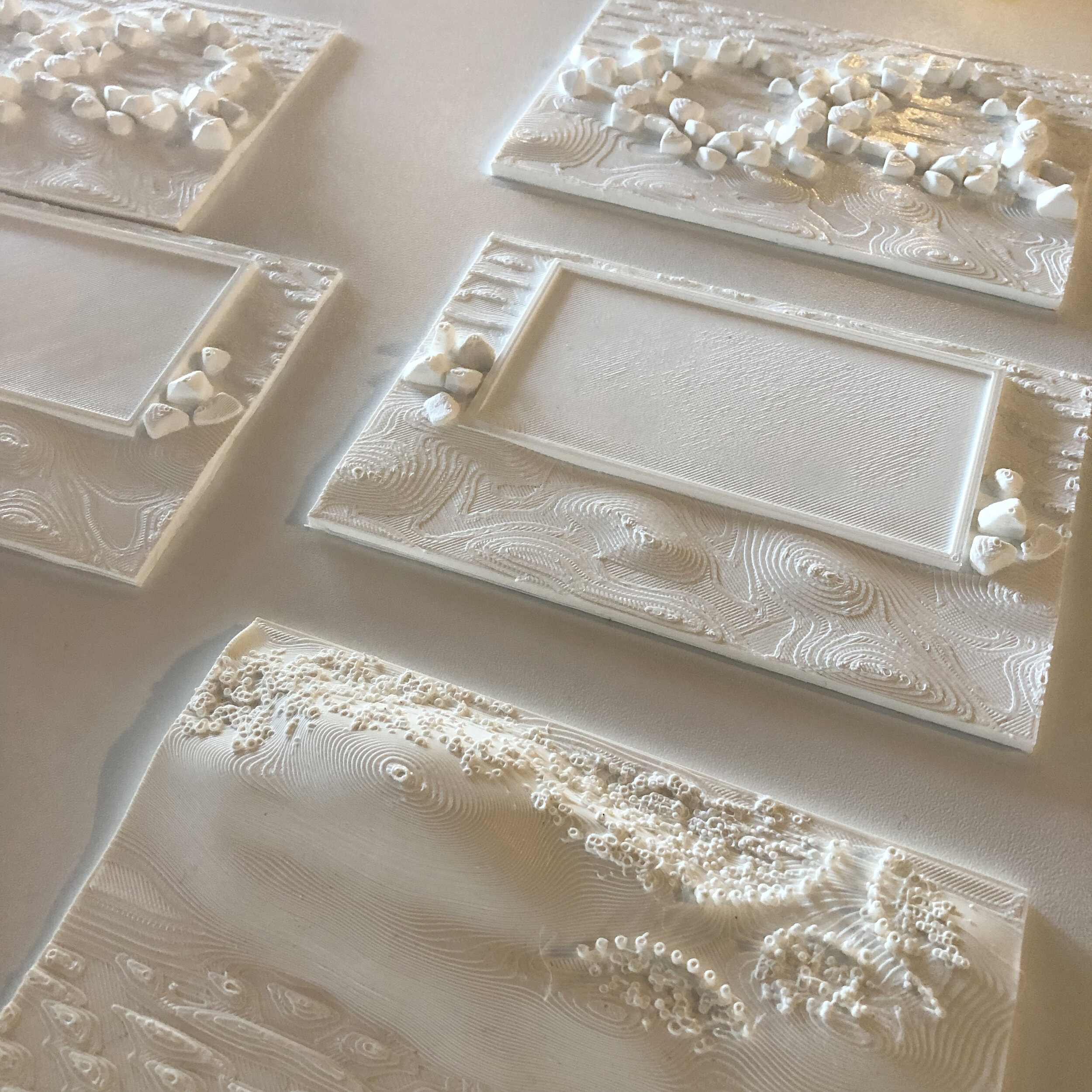

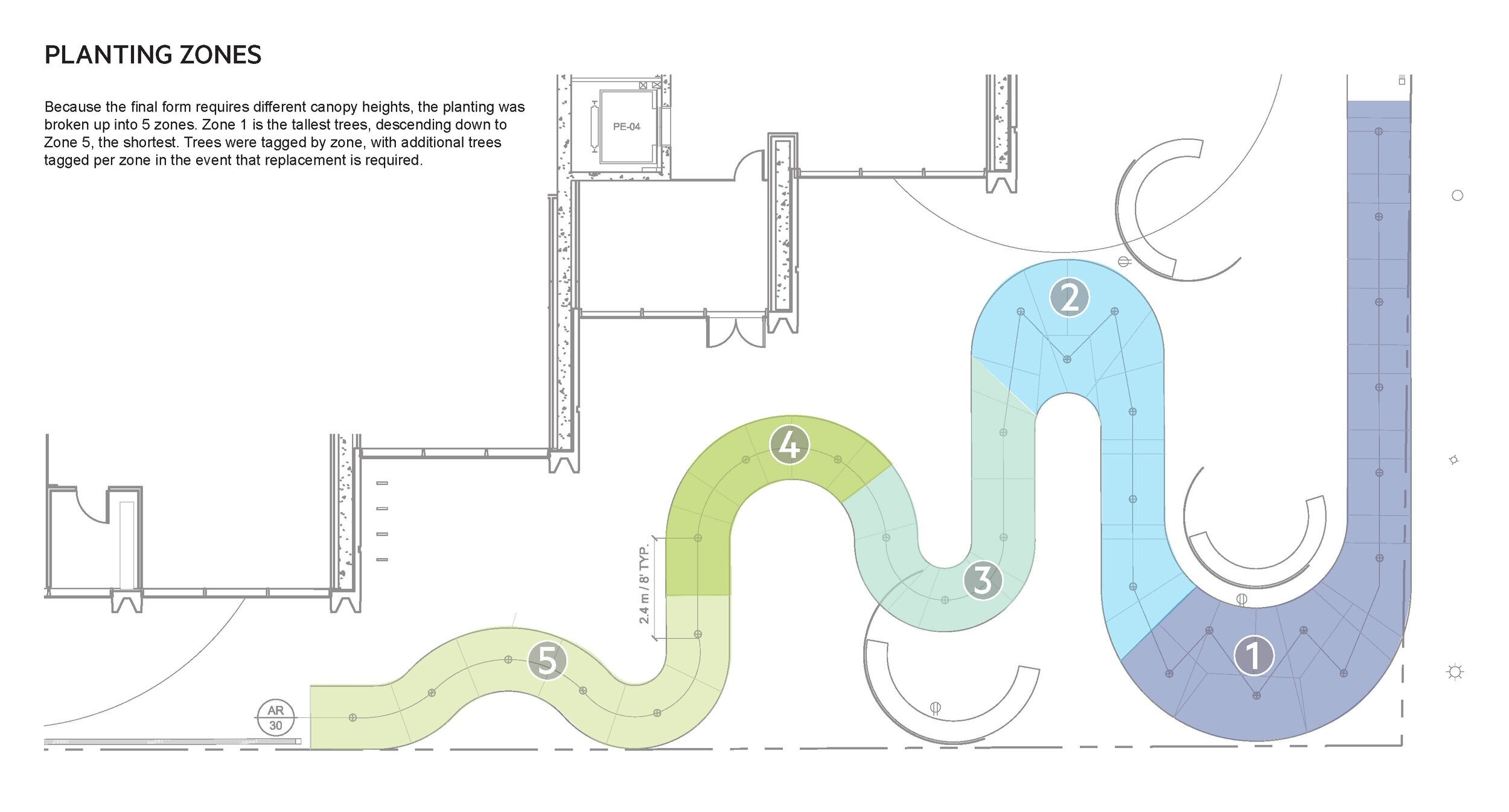

In order to better understand and convey these types of interventions, the Stoss team modeled, then 3D printed various configurations of the promenade, the seawall and the beach which allowed residents to configure their ideal sections. Seawall options included access ramps, a grand staircase, shaded overlooks, skate ramps and natural rocky shorelines.

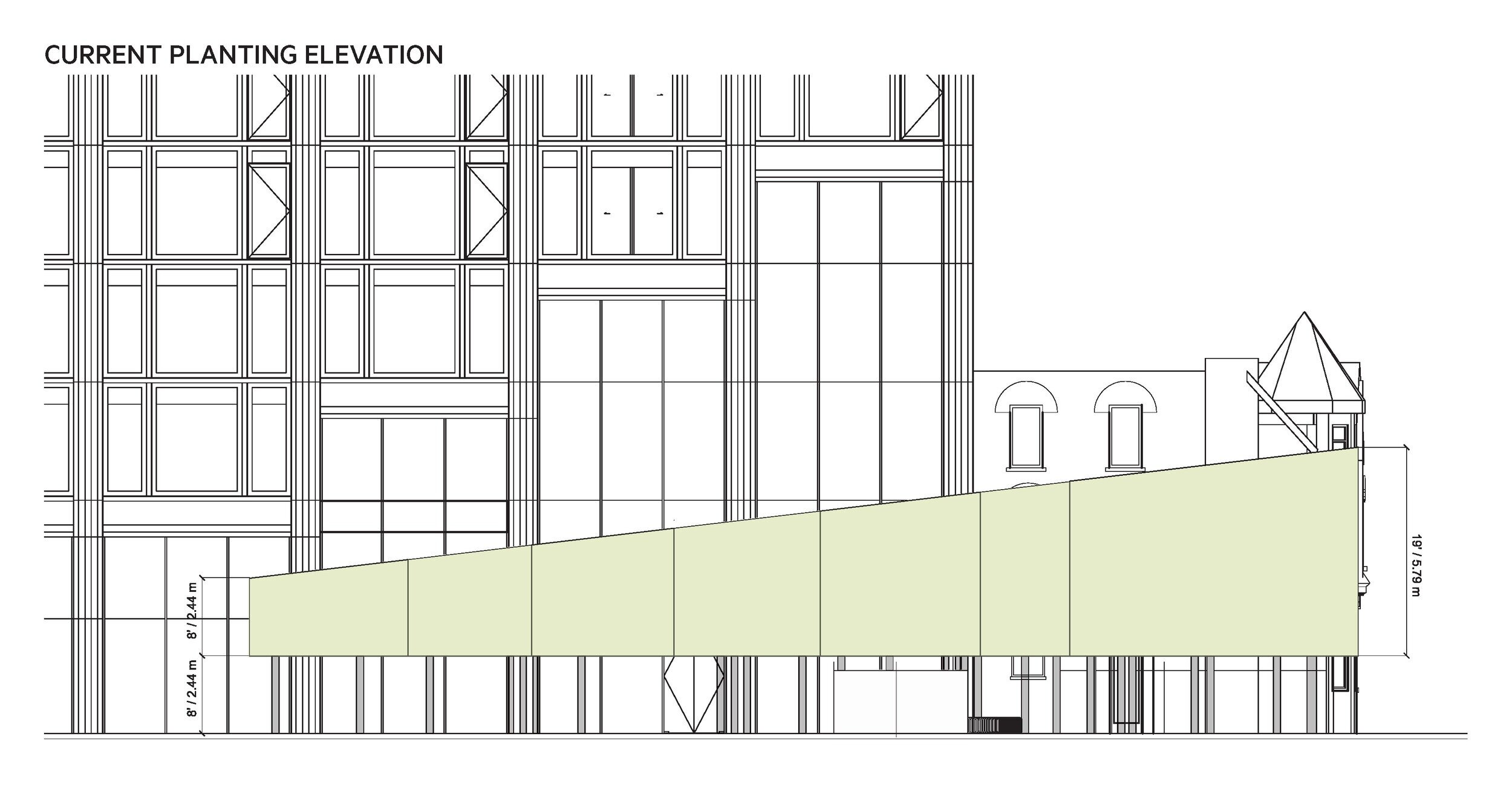

Seawall options paired with potential sea-level rise.

Public engagement poster.

During community events people were encouraged to play with the sections and share their preferred options which was then recorded by the design team. Not only did the team gather critical insight, but the community had an enjoyable time learning about the options and visualizing possibilities other than what exists there today. These types of exercises help transform a community’s mindset and pave the way for design innovation.

PROJECT DESIGN TEAM:

Chris Reed, Amy Whitesides, Lisa Hollywood, Rawan Alsaffar, Kanani D'Angelo, Chris Reznich