Until recently, green space was considered an ‘amenity’. But thankfully that perspective has shifted, accelerated by a global pandemic that exposed how essential access to quality urban green space is to human health. Today, we are reckoning with decades (and decades) of systemic lack of urban canopy in low income neighborhoods, finally confronting this poignant social and environmental injustice. Anyone living, working, and playing in these communities disproportionately bears the brunt of exposure to toxic, polluted air, water and the effects of extreme heat. Imagine sitting for a moment, at an exposed bus stop, on a sweltering 90 degree day surrounded by nothing but white-hot concrete. With no shade or shelter, and the constant bombardment of choking fumes from exhaust and dust, it takes but a few moments to realize that green infrastructure is absolutely not an ‘amenity’, but a necessity and right of every human being.

Los Angeles is a prime example of the scale of the problem. Tree-lined streets and backyards and public open space can generally be found in whiter, wealthier areas; meanwhile, low-income Angelenos of color are far more likely to be exposed to the high temperatures and air pollution that are associated with lower tree canopy. When compounded with disparities in access to healthcare and transportation, the existing inequity in tree cover across the city has major implications for the health, wellbeing, and quality of life of millions of L.A. residents. According to TreePeople the average existing canopy in the county is 20%, as opposed to the national average of 27%. Yet, in the majority of low income communities, we see averages of 5-8% tree canopy.

In 2019, the L.A. Green New Deal plan was proposed by the Mayor’s office. Amongst many other benchmarks, it strives to plant 90,000 trees by 2021, with the focus on increasing the tree canopy in low income communities by 50%. A tall order that can feel insurmountable when faced with real on the ground challenges. When analyzing typical streetscapes and urban intersections, the obstacles stack up with issues arising from the simplest of interventions. Large concrete driveway aprons, underground utilities and overhead power lines impinge even on simple tree planting efforts. Minimal soil volume, watering, and visibility issues, coupled with aesthetic and shared maintenance conflicts, derail more ambitious efforts and of course, removing any parking is a hot button issue. Yet, we have to navigate these barriers and find solutions to this intractable problem.

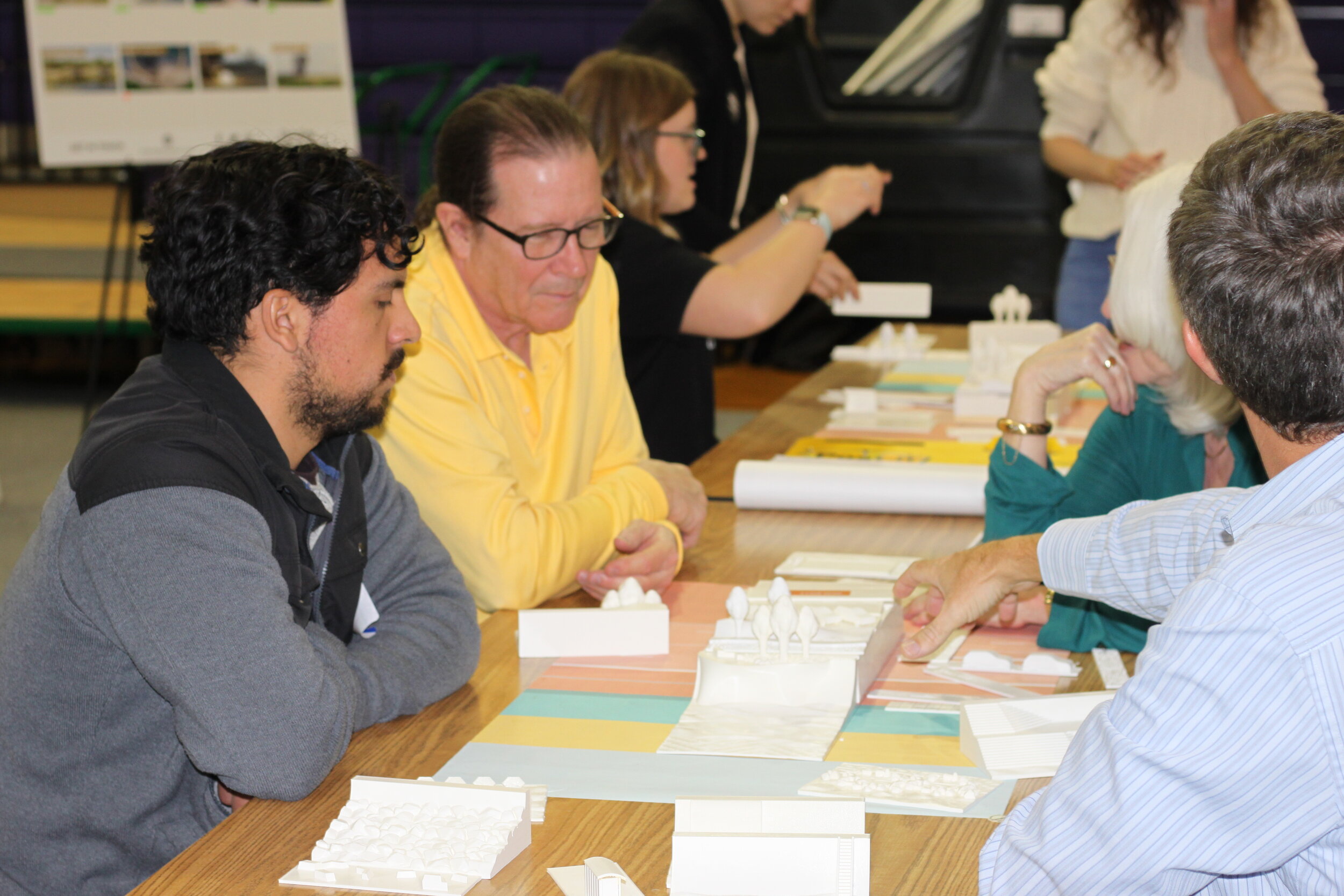

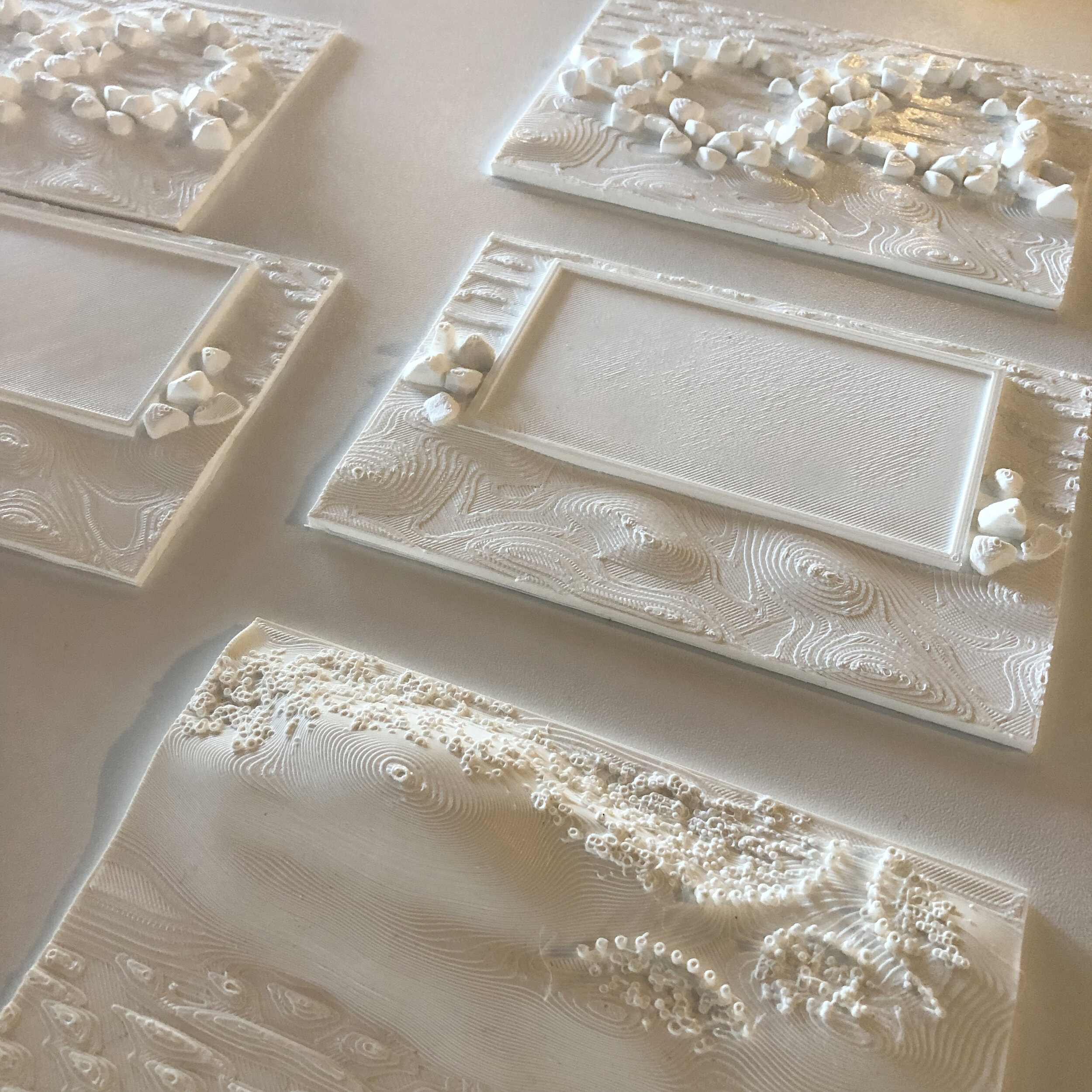

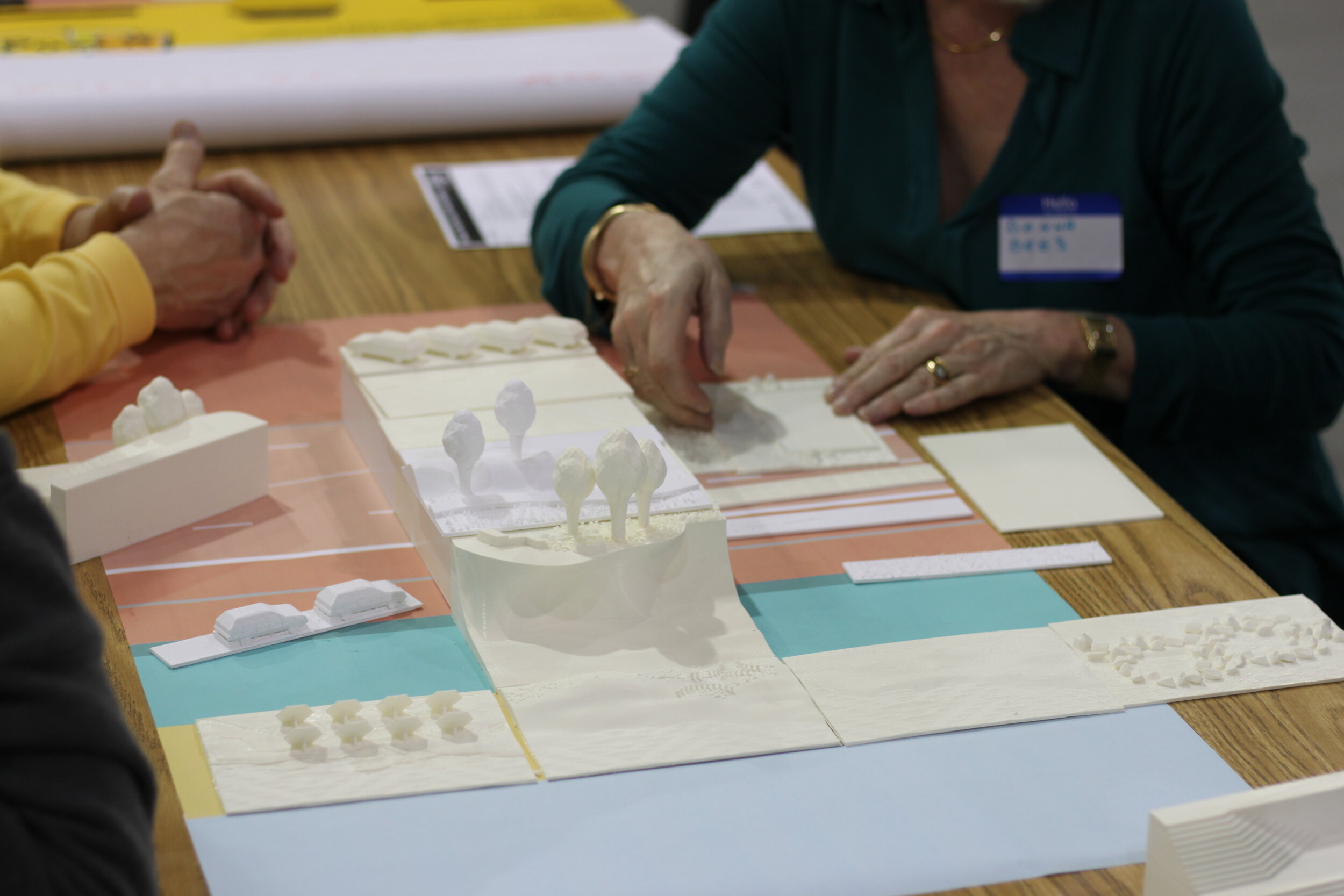

Recently, our team worked with a multidisciplinary team including City Plants, CAPA Strategies, TreePeople, the City's Chief Forestry Officer, as well as representatives from Streets and other city departments to help produce an Urban Forest Equity Streets Guidebook for the City of Los Angeles. The team’s research delves into the history of redlining and links disparities in tree cover with the long-term impacts of disinvestment and racial segregation. Working from case studies on ten streets (selected from across the city, and within some of the most socially vulnerable and those facing intense heat challenges, with a focus on South LA, East LA and the Northeast SF Valley to demonstrate varying conditions) the guidebook identifies challenges to implementation, potential trade-offs, and proposed improvements at multiple tiers of investment.

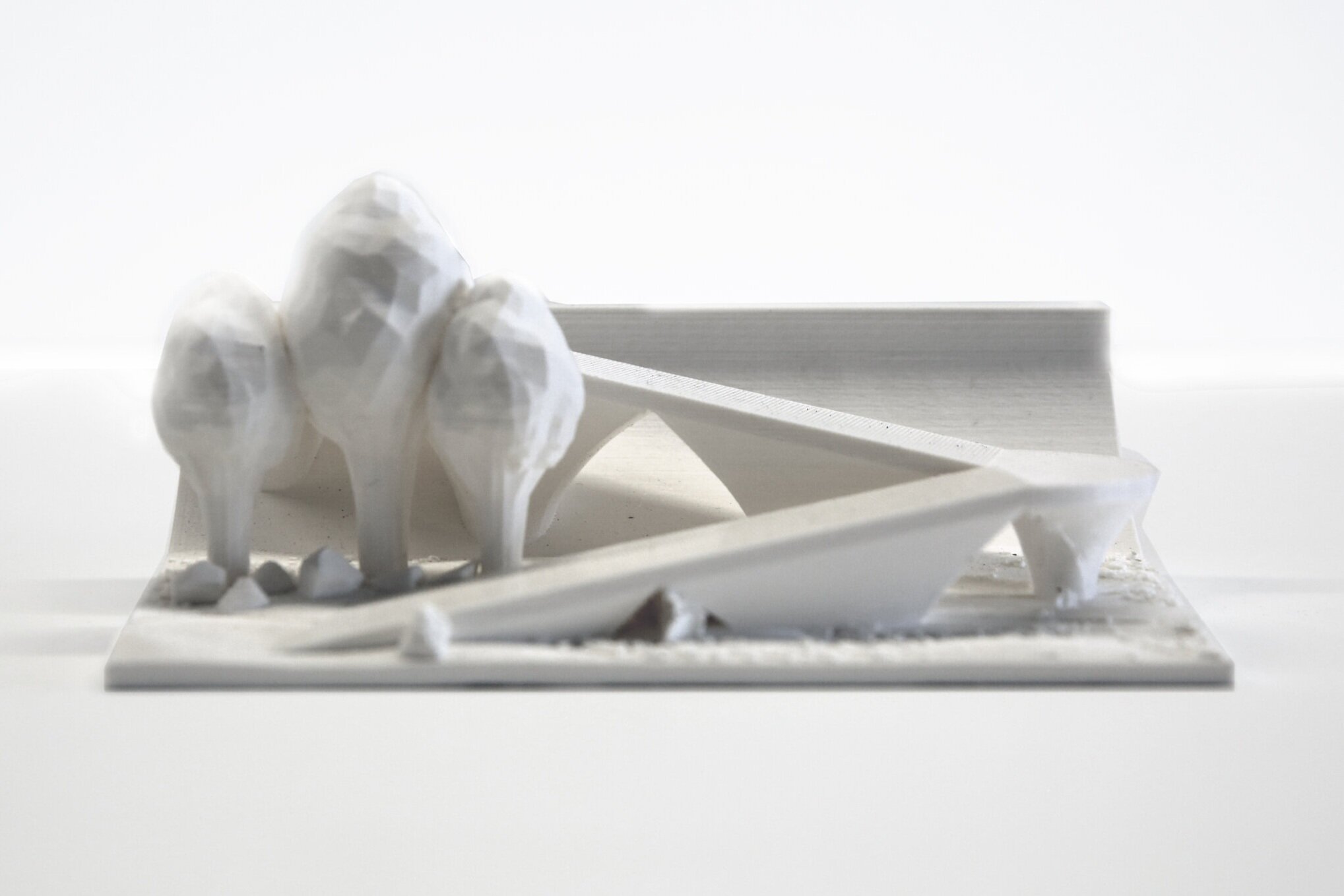

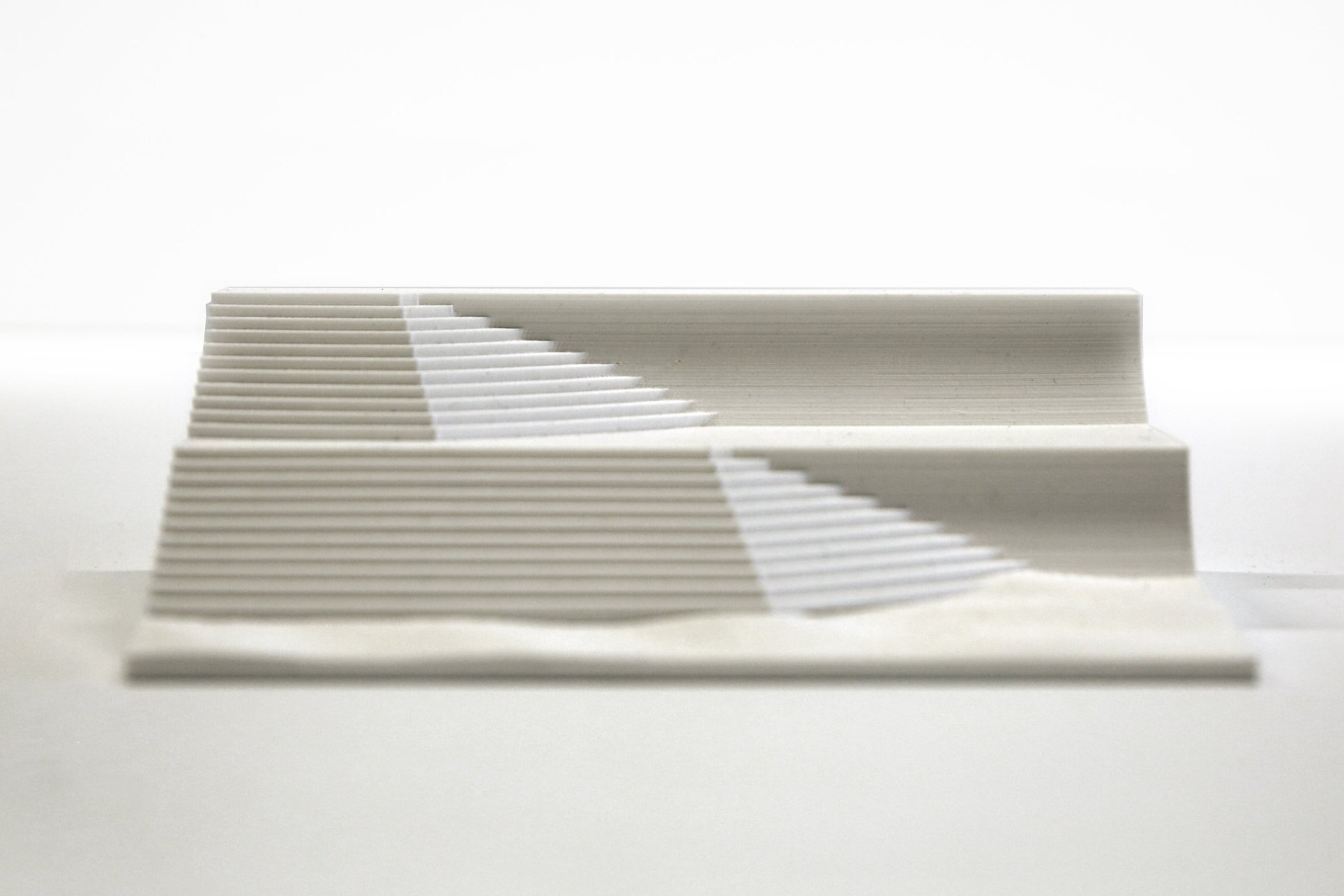

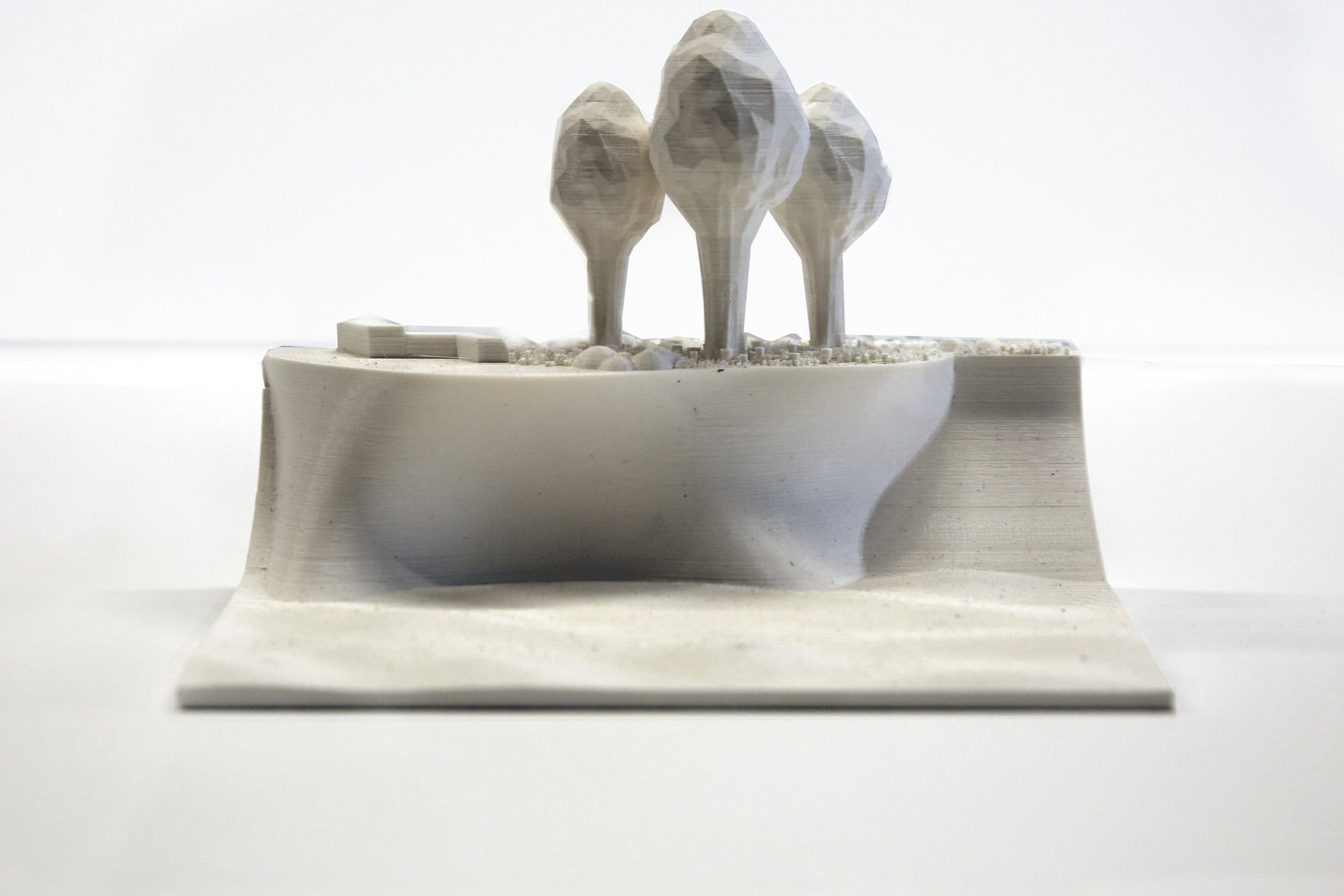

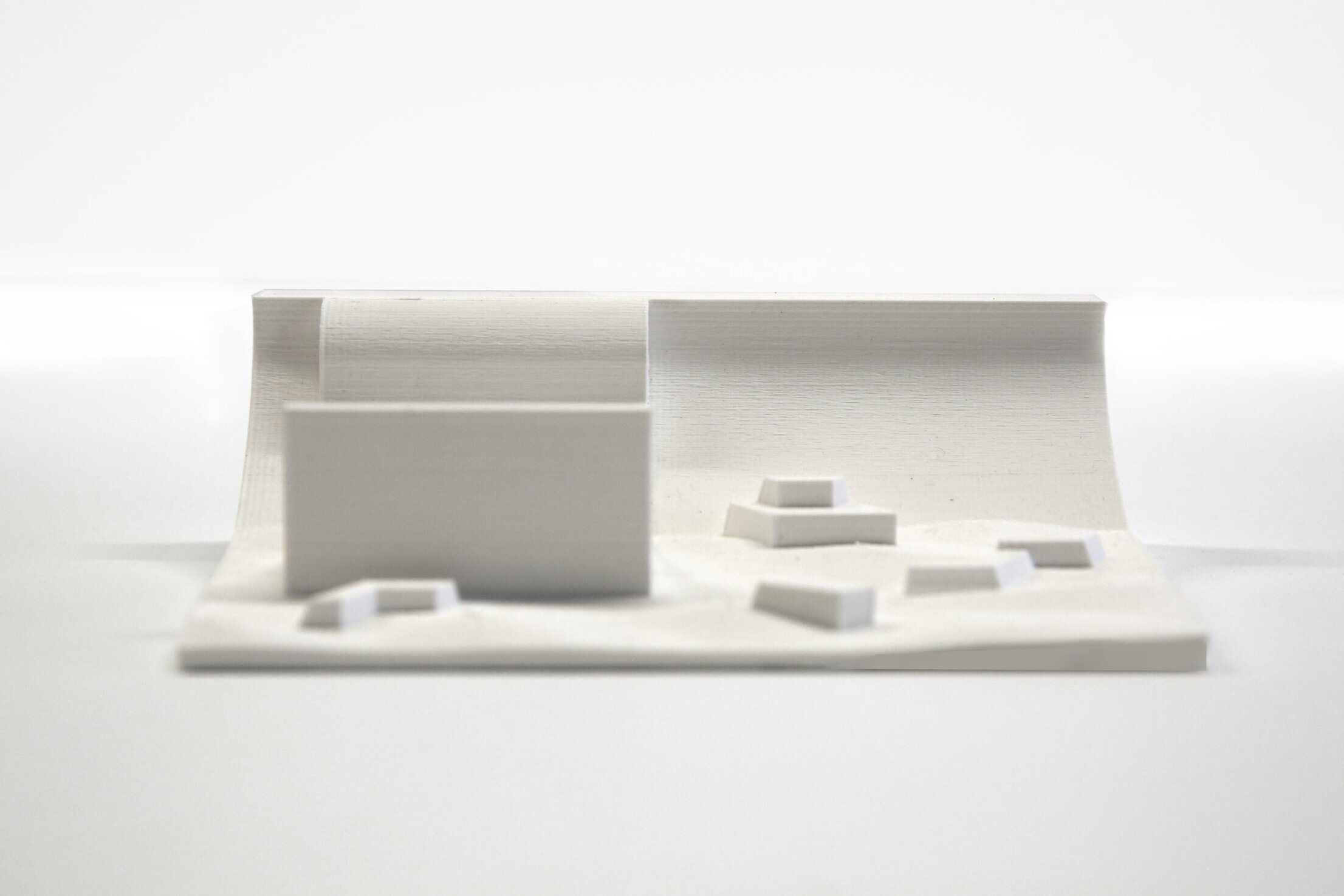

The plan breaks down improvements into 3 tiers. At tier 1, the team identifies opportunities that can be implemented with minimal cost and infrastructural change. For example, in Los Angeles available open parkways and private property were identified and solutions for easy low-cost planting presented. Yet, the reality is that even if all tier 1 sites were planted, the city would not achieve its 50% goal. Thus, the team proposed tier 2 interventions requiring more change and associated costs, and ultimately tier 3 solutions which involved new infrastructure like curb extensions and creating bike lanes and medians that would also help to calm traffic and filter stormwater run-off.

Before

Before

After

After

This framework offers a pragmatic, actionable plan to dramatically expand L.A.’s urban forest in the areas where trees are most urgently needed. It acknowledges the constraints and trade-offs while also providing solutions that can serve as a benchmark for other cities.